A Fourth Of July Story: Morrie Martin

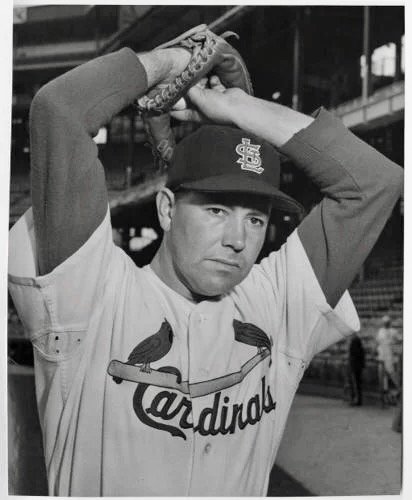

Morrie Martin

NOTE: This is a story I wrote several years ago. It was an odd situation, because when I went out to interview Morrie Martin in his home in Washington, Mo., he was bed-ridden and quite ill. Just two days after we spoke, as I was still putting together the story, he passed away. But I went ahead and finished the story and it ran in the paper on Memorial Day. I think it’s a story that is appropriate on this Fourth of July weekend.

Morrie Martin attended the baseball conference at the World War II Museum in New Orleans in November 2007. He was there with other WWII veterans and former major leaguers such as Bob Feller, Dom DiMaggio, Johnny Pesky, Lou Brissie and Jerry Coleman. He joined a panel discussion about the importance of the national pastime in the 1940s to a nation embroiled in world war.

But when he got there, the unassuming Martin, who made the trip from his modest ranch-style home in Washington, Mo., was hesitant about his place. He confided to his family, "I don't belong on that stage. Those guys are stars."

If a 'star" could be placed on a player for courage and diligence, Morrie Martin not only belonged, he deserved a front row seat.

Martin succumbed to lung cancer on Tuesday (May 25, 2010) in his home in Washington, Mo. He was 87. His baseball résumé is not impressive enough for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. "Lefty" pitched through 10 seasons in the big leagues, won 38 games, lost 34. His best season was 1951, when he went 11-4 with a 3.78 earned run average for the Philadelphia Athletics.

But on a national holiday that commemorates those who made the ultimate sacrifice to protect our freedoms, it's not Martin's big-league life that bears highlights. It's the manner in which he arrived at it.

From tiny Dixon, Mo., to the daunting beaches of Normandy, from the bone-chilling terror of the Ardennes Mountains region through the Siegfried Line, he survived a world war to rub elbows with teammates like Jackie Robinson, Duke Snider, Nellie Fox and Stan Musial.

No one traveled further to get to the big leagues. No one accomplished more.

Martin grew up on a farm in Dixon, in the south-central part of the state. His dad was a carpenter, and his family had precious little in the midst of the Great Depression. He nearly died as a child after contracting diphtheria, and later survived being struck by lightning. He was a resilient kid, and he had a rifle for a left arm.

"My dad would tell me that I could hit most anything I threw at," Martin said during a recent interview. "I guess I was around 8 or 10 years old, and my dad would tell me we needed some meat on the table. So, I'd go out and hunt for rabbits. I'd hit them with a rock and bring them home.”

During the summer of his 17th year, Martin traveled with a local amateur baseball team to play a college team in Rolla, Mo. He pitched a shutout, striking out "20 or 21" batters. When the game ended, the Rolla team was to play a team from St. Louis in a second game. The Rolla manager asked Martin whether he would pitch the next game for Rolla. He tossed another shutout and struck out 20 more.

When the game ended, a man asked, "Morris, how would you like to play professional baseball?" The inquirer was Wally Schang, a former big league catcher and scout for the Chicago White Sox.

The following February, in 1941, Martin received a telegram asking him to come to spring training in Leesburg, Fla. He had never traveled farther than St. Louis, but he took the chance.

When he arrived in Florida, he was met by Schang, who told the unassuming kid to warm up with Ralph "Red" Kress, a former St. Louis Browns shortstop who was trying to extend his career with the Sox.

Martin wound up and fired a fastball directly over Kress' head, the ball sizzling by as he reached — belatedly — with a mitt. Kress stood up, tossed his glove aside and exclaimed, "Sign him up!”

A farm boy who could play country hardball like that could move up quickly if the circumstances were right. And with the nation pulled into a world war and baseball scrambling to replace drafted personnel, opportunity was knocking.

The young southpaw was assigned to the Grand Forks Chiefs of the Class A league, and he made another splash, playing in the All-Star game and fashioning a 16-7 record with a 2.05 ERA. In 1942, he was catapulted to the Class AAA St. Paul Saints of the American Association, within arm's length of the big leagues. "I was pretty sure I was about go get called up to the majors," Morris recalled.

But before the Sox could call, the local draft board and Army beat them to the punch. More than 4,500 professional baseball players served in the military in World War II, including some 500 major leaguers. Many of the drafted players did little more than play ball, as the military used their talents to entertain the troops.

Some were not as fortunate. Martin was sent to Camp Polk in Louisana and assigned to the First Army's 49th Combat Engineers. In 1943, his company shipped out to Oran, Alergia, in North Africa, to participate in "Operation Torch," a prelude to the invasion of Italy.

Although Martin's outfit was not directly involved in combat in Oran, the environment was dangerous and chaotic. Local bandits were known to slip into Army barracks and kill soldiers for their possessions. "It was scary over there," Martin said.

As it turned out, it was a picnic compared with what the 49th would face next.

Leaving North Africa in the spring of 1944, Martin spent time in England before his company assumed a lead role in the Normandy invasion on June 6. Bobbing on the stormy, choppy English Channel for hours, the division of engineers landed at dawn, the first wave to come ashore at "H" hour.

Some men were so seasick, they could hardly walk, including Martin's buddy, Al Link. The 5-foot-11, 175 pound Martin helped Link get ashore, carrying his 60-pound barracks bag, rifle and other equipment — in addition to his own. With no infantry or armor to protect them, the engineers worked to clear gaps through the beach barriers and make their way inland, ahead of the assault wave.

During the D-Day operation, Army engineers suffered casualties of over 40 percent. Words cannot adequately describe the terrifying nature of the operation. Fifty-six years later, Martin still could not talk about it, other than to shake his head and say, "You can't imagine.”

But for the 49th, it was only the beginning of a journey that would include the taking of a key bridge in Sainte-Mère-Église, France (featured in Band of Brothers), liberating the port city of Cherbourg before taking part in "Operation Cobra" at Saint-Lo, a strategic crossroads so heavily bombed it became known as "The Capital of Ruins."

It was there, Martin was hit by shrapnel, suffering wounds in his arm, hand and neck. The finger on Martin's pitching hand remained permanently bent, but he claimed the deformity helped him later to throw a sharper curveball. "It wasn't too bad," said Martin, who received a Purple Heart. "They just patched me up and I went right back at it."

From there, Martin and his company advanced into Belgium in the midst of a horrific, arctic-like winter for the Battle of the Bulge, the largest and bloodiest battle American forces took part in during WWII.

Martin suffered frostbite on his feet. "I couldn't hardly walk," he said, "they were in such bad shape." That Christmas Eve, he spent the night huddled against a tree, covered in snow, loath to move for fear of being spotted by snipers.

When the weather broke and the Allies prevailed, Martin's troop of engineers advanced to the German border and the vaunted Siegfried Line, extracting a path through the myriad of pillars and steel beams constructed to repel the Allies. Another savage fight led to the capture of Aachen, Germany, where the combat went house to house.

Martin did his best not to dwell on what he did and what he saw. How else could a soldier put one foot in front of the other, face one day after the next.

"When the battles started, you remember how they got started," he said. "You remember the noise and the guns, and the artillery going off. But then I guess you just block it out of your mind. After everything starts, it just goes blank. I don't remember a lot of things. I know it was hell, I remember that."

Martin and the 49th later helped capture the Ludendorff Bridge at Remagen, the last bridge standing on the Rhine. During operations, Martin often volunteered to replace one of his comrades on dangerous duties.

There, the odds finally caught up with him when he was hit in the leg by machine gun fire. The wound became infected, and he was sent back to a hospital in Saint-Quentin, France. He remembers waking up as a nurse informed him they were planning to amputate his infected leg.

The nurse had looked at Martin's bio and saw he was a ballplayer, so she suggested an alternative. She told him he could refuse the operation and, instead, take a chance on being treated with a still-experimental infection-fighting drug — penicillin. His leg was saved.

"I owe that nurse my leg," he said.

Once he was able to walk again, Martin was sent to a hospital in Paris for two months of convalescence. He was then granted a furlough and shipped home on Aug, 2 — his father's birthday. His father often told him, "That was the best birthday present I ever got in my life."

During his furlough, he met his future wife, Loni, who would become his shelter from the storm. The two exchanged letters and kept in touch and four months after Martin was discharged, they were married in February 1946. Their special bond reached its 64th year three months ago.

After moving to Washington, they reared four daughters and 15 grandchildren. The war would continue to taunt Martin on occasion; never completely going away. But Martin refused to let the war define his life. He made his way back into the main stream and back into baseball.

In 1945, the Brooklyn Dodgers acquired Martin and by 1949, nine years after he signed that first contract, the hard-throwing kid from Dixon made it to the big leagues. The first batter he faced was the Cardinals' Stan Musial — and he struck him out.

Martin was 1-3 in 10 games for the Dodgers in '49. He spent the next season back in the minors. After going 11-4 for the Philadelphia A's in 1951, he appeared on his way to bigger things before a collision with Cleveland catcher Jim Hegan ended his season.

He ran into more bad luck in 1952. After just five starts, he was struck by a line drive that broke the index finger on his pitching hand. After the injury, he spent most of his career in the bullpen. He had 10 wins and seven saves for Philadelphia in 1953, then spent time with five other teams, including the Cardinals.

He appeared in 21 games for St. Louis over the 1957 and 1958 seasons, going 3-1. His major league statistics are embellished by an 85-58 record and a 3.09 ERA over 10 seasons in the minor leagues.

Martin never sought recognition for what he did during the war; he never brought it up. When Martin attended the conference in New Orleans in 2007, it was the first time members of his family ever heard some of the details of his service. Revisiting those moments, which had been kept under lock and key, along with his Purple Heart, oak leaf cluster and five bronze stars, was overwhelming for Martin.

"It really upset him," Loni Martin said. "He wasn't himself for a while, It took him a couple of weeks to get over that."

After retiring from baseball in 1961, Martin became a salesman in the meatpacking industry. He coached and organized youth baseball, indulging in his passions for hunting and fishing. After surviving the challenging detours, he settled into a good life. In June 2009, he was diagnosed with lung cancer.

"He was a wonderful man," said Zach LaBoube, Martin's grandson. "He never wanted any attention, never considered himself anything special. But he lived an amazing life."

The sacrifices Morrie Martin made, the feats he accomplished, won't warrant space in Cooperstown, and they didn't bring fortune or fame. In his own assessment, as Memorial Day was approaching, they were nothing to go on about.

"We had a job to do and we did it," Martin said just days before he passed away. "I don't have regrets about the time I missed in baseball. I'm proud of what we did. I'd do it again."