Remembering Whitey Herzog - The Pride of New Athens

Members of the 1948-49 New Athens High basketball team. TOP ROW: (44) Jim Womack, (11) Charles Schreiber, (10) Bob Klingenfus, Coach Lonnie Woods, (30) Bill Hoffman, (40) Dale Schneider. BOTTOM ROW: (22) Ardell Schoep, (30) Jim Schmulbach, (55) Bud Wirth, (20) Relly (Whitey) Herzog, (33) Bob Waeltz, Don Ragland.

Whitey Herzog would have turned 94 today. He is dearly missed, by Major League Baseball, by St. Louis, by his family, by his 1-2-3 Club brothers and certainly by me.

Only my dad taught me more about baseball. No one told stories like Whitey,. They were sometimes inappropriate, frequently irreverent, often hilarious and always captivating. His exterior could be rough, but his heart was gold.

I was fortunate to be a sportswriter when manageed, blessed to spend time in his office before and after games, to talk baseball and lots of other things, to see him transform the Cardinals from annual underachievers to ballpark-packing pleasers.

The trades, color and excitement were special, a time that might never be matched. This is a story penned when Herzog was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2010, a perspective on who he was, why he was and what he meant to a lot of people:

GROWING UP HERZOG

They would always wait. Maybe they'd play catch, or bottle caps. Maybe they'd kill time by trading cards, or arguing over who was better, Ted Williams or Stan Musial. Maybe, if they were lucky, the Washington Senators were playing the Browns in St. Louis, and Sens pitcher Mickey Haefner was holding court at his house just beyond center field.

But the kids gathered on the grade school sandlot would wait each morning before beginning the daily ritual. They'd wait for the Herzog boys to show up.

Then Relly would come riding up on his bicycle, a dusty first baseman's glove dangling from the handlebars, older brother Herman alongside. And the choosing could begin, one Herzog to a side, two or three games to a day, another summer in New Athens, Ill. Who knew it would lead to a special summer in Cooperstown, N.Y.?

Fans throughout baseball know him as Whitey. In St. Louis, where he managed the Cardinals to a World Series championship and three pennants, his industrious brand of baseball is known as Whiteyball. Baseball insiders, who have been around to listen to his colorful stories and blunt opinions, know him as the White Rat or simply Rat.

But in New Athens, a 1.8-square-mile slice of rural Midwest, pinched between farmland and Peabody strip mines, skirted by the Kaskaskia River, Dorrel Norman Elvert Herzog was — and still is — "Relly."

"That was his name, that's how everybody knows him," said Kent Fullmer, who was part of the gang to meet at the sandlot.

"That's what his mom called him. He was never Whitey until he went down to play in Oklahoma."

A sportscaster in McAlester, Okla., gave Herzog the nickname of Whitey, referencing his bleached-out shock of blond hair. The "White Rat" label was added in the spring of 1955, due to his resemblance to former Yankees pitcher Bob (The White Rat) Kuzava, who also featured a flat-topped coif of blond hair.

Now poised to enter the Hall of Fame as a baseball manager and executive, Herzog did not have an illustrious major league playing career. In eight seasons, he appeared in 634 games, batted .257 and had 25 home runs and 172 runs batted in.

But on those sandlot fields in St. Clair County, where the gang always waited for the Herzogs, Relly was one of the best the town ever has known.

"I really think we had it better growing up," Herzog once said, reflecting on that small-town childhood. "For kids today, everything is organized. I don't see kids having as much fun as we used to have."

CAN BREATHE IN A SMALL TOWN

Situated 40 miles east of St. Louis, New Athens has a population of slightly more than 2,000, according to recent figures. The pace of life hasn't changed much over the years. There were some 1,500 residents when Herzog attended New Athens High. His graduating class picture still hangs above the second-floor office at the high school, between other framed classes. The Class of '49 consisted of 34 kids; last year's graduating class had 54. No one is a stranger.

Fifty percent of the community is of German descent, although they sometimes refer to themselves as 'stubborn Dutch." They are loyal, proud and resilient people. They live in small frame houses and live life in small portions. They work long days, drink long necks and drive hard bargains.

When the Mound City Brewing Co. thrived in town during the late 1940s and early 1950s, as many as 16 taverns were dispersed around the town and its perimeter. In 1953, when Herzog came through New Athens with a U.S. Army baseball team, he took some teammates around and predicted who would be sitting where at each bar they visited. He batted 1.000.

The Herzog home still stands at 603 South East Street. His younger brother, Codell "Butzy" Herzog, lived in the house until he passed away in February, 2010. A character in his own right, Butzy Herzog was more of a fan than an athlete. He signed up to play baseball at New Athens High one season, mainly because players got out of class early to prepare for a game or practice. In his only at-bat for the Yellow Jackets, Butzy tapped back to the mound and walked directly back to the dugout.

"He didn't even run the ball out," laughed Dennis Schotte, a longtime friend. "He just went and sat down, and that was it. He never batted again."

But Butzy Herzog loved the Cardinals and he could cite baseball statistics, chapter and verse. When Relly was hired by owner Gussie Busch to manage the Cardinals in 1980, Herzog didn't know much about the players, having managed the American League Kansas City Royals for the previous five years.

Before his first game as the Cardinals' skipper, Relly Herzog told Butzy to make out the lineup card. He did, and the Cardinals won the game in extra innings on a home run by George Hendrick. From that point on, Butzy Herzog liked to brag he was 1-0 as a big-league manager. He sometimes wore a Cardinals "Herzog" jersey with "24½" on the back, a takeoff on his brother's No. 24.

DIFFERENT PERSONALITIES

Herman Herzog, whose proper first name is Therron, was an outstanding athlete, a hard-hitting, good-fielding shortstop. Like Relly, he signed a pro contract and played a year of minor league baseball in 1954, after a stint in the service. But Herman, who had a slight speech impediment as a child, was not as confident and audacious as his older brother.

"Some people in New Athens thought Herman was a better high school player than Relly," Schotte recalled. "But they were two different personalities."

On the other hand, Relly — or Whitey, if you insist — determined early on he would follow the bouncing baseball as far as it might take him. If college entrance exams were based on savvy and street smarts, he could have attended any college in the land. But his intelligence notwithstanding, he never focused much on studies.

He sometimes skipped school, thumbed a ride up Route 13 to Belleville and took a bus to Sportsman's Park. For $1.25, he would sit in the grandstands and study his heroes, players like the Browns' Vern Stephens or the Cardinals' Musial and Enos Slaughter. He'd get there early, sneak into the stands and snare batting practice balls. He'd keep one or two, sell the others for $1 apiece, go home with money in his pocket and balls for the sandlot.

"The principal would never tell my mother," Herzog said. "He'd call me up to the office and we'd end up talking about the ballgame. I wanted to be a ballplayer, although at the time I was probably a better basketball player.

"But I didn't pay much attention to the books. As long as I stayed eligible and got passing grades, I wasn't worried about going to college."

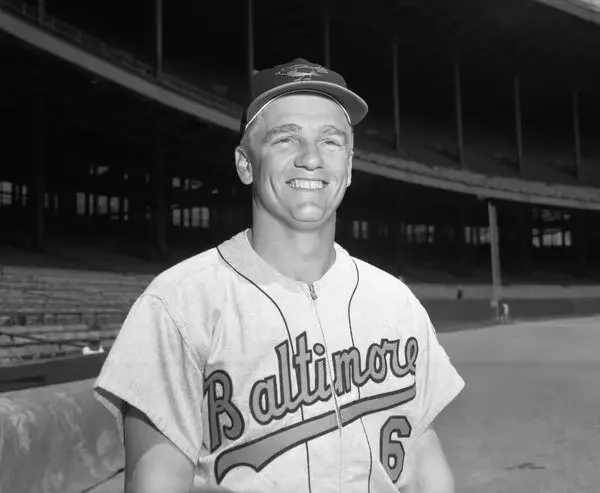

Herzog batted .291 in 113 games with the Baltimore Orioles in 1961. He played eight seasons in the majors (1956-63) for four different teams - Washington, Kansas City, Baltimore and Detroit. He once said, “Baseball has been good to me since I quit trying to play it."

LADIES MAN

Edgar and Lietta Herzog did their best to make their limited ends meet and raise three boys. Edgar worked at the Mound City brewery until it burned down in 1951, then took a job on a highway crew. Lietta worked at a shoe factory in town.

If the Herzog boys had one nickel to rub against another, they had to hustle to get it, and the precocious Relly was quite capable. He got up at 6 each morning to deliver newspapers on his bike. He drove up and down the streets and sold bakery goods out of a panel truck. He dug graves at Oak Ridge Cemetery, and eventually he worked at the brewery, too.

"Whitey always was outgoing, talkative and friendly," recalled Belleville native Barney Elser, who played ball with and against the Herzogs during their high school years. "He was more outgoing than Herman, although Herman was always a very friendly fellow as well. But Relly was the more talkative one.”

Relly was popular with the girls, a guy's guy, a familiar face to everyone in town. In short, the boy had talent.

"He was quite a singer when he was a little boy," said Fullmer. "They would have talent contests and his mom would play piano and Relly would sing. 'Josephine,' that was his theme song."

By the time he attended high school, Relly Herzog's theme song was more like "Take Me Out to the Ballgame." Playing for coach Alonzo J. Woods at New Athens High, he was a two-sport standout — a point guard on the Yellow Jackets' basketball team, an outfielder/first baseman/pitcher for the baseball team. The baseball field behind the high school is now named Whitey Herzog Field, a tribute to its famous alum, who donated money to renovate the grounds.

Although the high school now uses a newer gym for the varsity teams, the facility that the Herzog boys played in still functions as an auxiliary gym. The caramel-colored wood floor is still in place, the brown ceramic-coated brick walls still stand and oversized white wooden backboards are still affixed to the walls.

During his senior year, the 5-foot-8, 130-pound Herzog was captain of a Yellow Jackets basketball team that went to the regional finals. The 1949 edition of Vespa, the New Athens High yearbook, notes, "Relly was a constant threat both offensively and defensively. He possessed an uncanny shooting eye and his ability to make those crucial baskets helped the team through many a close game. His speed and ball-handling ability will make him one of the main cogs of the 1948-49 team."

Herzog wasn't the only cog for New Athens. Edgar "Bud" Wirth, a 6-4 post player, led the team in scoring. And, unfortunately, Herzog's shooting eye was not always uncanny. In the Illinois regional final, shooting against glass backboards for the first time, Relly went 0 for six from the free-throw line and the Yellow Jackets lost by one point.

Nonetheless, Herzog was good enough to draw recruiting interest from schools like St. Louis University and Illinois. He remains a fervent basketball fan and knows as much about hoops as anyone you might meet. But his dreams were elsewhere.

HARD TO SWALLOW

During his junior year, the New Athens baseball team advanced all the way to Peoria and the state championship game with Granite City. Herman Herzog was the leadoff batter, and Relly batted third most of the time, leading the team in hitting with a .584 average. A southpaw, he also occasionally took the mound, tossing a no-hitter in a 4-0 win over New Baden.

According to Vespa, he 'specialized in curve balls he threw with hairbreadth control." He also learned the hard way that baseball gods do not always smile in one direction. In the state championship game, playing under lights for the first time ever, Herzog lost a ball in the glare in center field and it fell for a triple. Two runs scored as Granite City took a 3-1 lead in the third inning.

In the seventh, after two New Athens batters had reached, Relly hit a line drive right at the third baseman, and right into an inning-ending double play. Granite City went on to win 4-1.

Baseball acumen was widespread in small-town America during the postwar 1940s, particularly in Southern Illinois. Three of Herzog's teammates were selected to the 1948 all-state team, including Wirth, second baseman Emil Klingenfus and third baseman Ardell Schoeppe. Five players from Granite City were named to the team. Relly Herzog and fellow outfielder Bill Schreiber were second-team honorees.

The disappointments of those postseason losses stayed with Herzog over the years, compounded by postseason disappointments in Kansas City. When Herzog's Cardinals beat the Milwaukee Brewers in the seventh game of the 1982 World Series, he felt 100 pounds lighter.

"When we were able to win the Series here, I thought back to my high school days, that we went there twice and the way we lost," Herzog said. "And it really was a load off my mind.”

COULDN’T COMPETE WITH MANTLE T

After high school graduation, Herzog signed a contract to pursue his ball-playing aspirations with the New York Yankees. He reported to the Sooner State League team in McAlester, Okla., where he batted .279 that initial summer. The following season, the summer of 1950, he batted .351.

There was just one problem. The Yankees signed another good-looking high school outfielder in 1949, a kid from Commerce, Okla., named Mickey Mantle. During that same summer of 1950, Mantle batted .383 with 26 home runs for the Western Association team in Joplin, Mo. By the summer of 1951, Mantle was in the outfield at Yankee Stadium — and he wouldn't be going anywhere soon.

Herzog would not reach the big leagues until 1956, after he had been traded from the Yankees to the Senators and after he batted .289 with 24 homers for Class AA Denver. His playing career eventually ended prematurely in 1963. During spring training with Detroit, he caught a virus that affected his inner ear and caused dizziness.

Herzog was only 31, but after hitting .151 in 52 games for the Tigers, he was done playing. Perhaps it was as early as 1953, however, that Herzog demonstrated his true calling. With the Korean conflict going on, he interrupted his baseball pursuits to join the Army Corps of Engineers. Stationed at Fort Leonard Wood, Mo., he became manager of the camp baseball team and once beat a Fort Carson, Colo., team managed by Billy Martin.

He also revealed his uncanny ability to manage a game situation. On one occasion, his baseball Band of Brothers wanted a holiday pass to drive in to St. Louis and watch the Cardinals play, but they were scheduled to play a doubleheader in camp. Herzog recruited a few soldiers to flood the baseball field with hoses during the middle of the night. The doubleheader had to be canceled because of the wet grounds. You might say Herzog called for an intentional pass.

'JUST WHITEY'

Along the way, no matter where baseball has taken him over the past many years, Whitey Herzog has never forgotten his Relly Herzog past. During his years managing, he would sometimes hear someone call "Hey Relly!" from the stands, and immediately know it was a friend from New Athens.

By the end of his high school days, he was dating Mary Lou Sinn, a year behind him in school. She had once given him a valentine card when he was in sixth grade; sometimes love takes time to germinate. The two were married in 1953 and raised three children.

Kids in New Athens always knew when Herzog was in town because his Edsel would be parked outside the Sinn house. "He would come home and I was still in high school at that time, and a bunch of us would get together with him and we would play ball right there in the street," said Jim Newman, Mary Lou's first cousin, who lived next door. "He would hit us fly balls and things and give us pointers. He used to do that a lot.”

Dennis Works, a 1977 graduate, remembered when his mother and father ran the M&M Lounge in New Athens. "I'd come in and walk in back and Whitey would be sitting there with some friends," Works said. "We'd see him a lot. But when he's here, it's not like the president is in town. It's just Whitey, and, 'Hey, nice to see ya.' "

A group of more than 20 New Athens residents are making the trip to Cooperstown for the induction ceremonies, some of them by bus. Relly Herzog already is in the New Athens Hall of Fame. His neighbors won't miss a chance to see him go into baseball's Hall of Fame.